As Your Resource For Self-Development

- The Optima Bowling Coach (2025)

Teacher Student Relationship

(Page Updated 11/6/23)

The problematic teacher-student relation was the purpose driving the Optima Bowling Coach original site focused on bowling coach business research and development. Now (2023), the focus is the teaching and learning dichotomy, the external or teacher-directed and the internal or student-determined progression of the topic, teaching, knowing, understanding, and creating.

As presented on the New View of Behavior page, research shows that the bowling coach-athlete relation problem resolution is best perceived as a behavioral problem from the point of view of the behaving organism. To engineer a solution, I will apply the Hierarchy Perceptual Control Theory structure of behavior as the control of perception. The HPCT model of subjective (abstract) and objective (concrete) perceptions will serve as the psychological framework for configuring the course of action to produce, control, and maintain an individual’s reference perceptions.

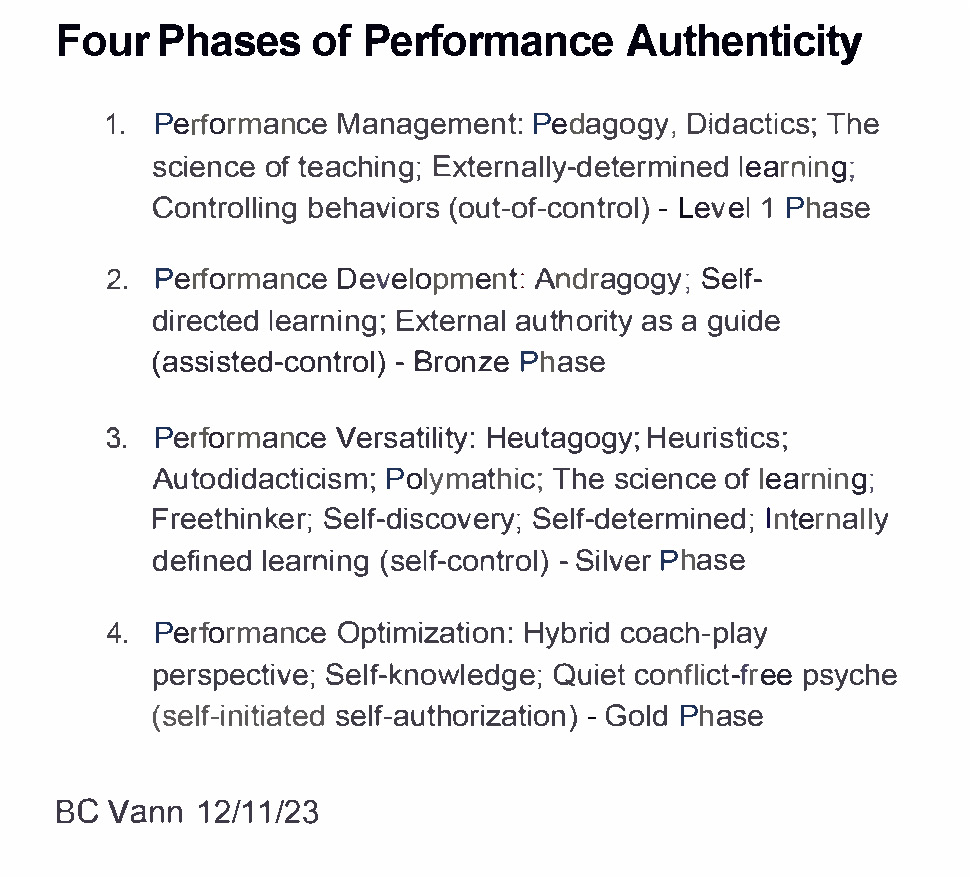

Four Performance Phases

Performance has four phases, but for wholeness sake, you may have noticed that I have applied research on education theory as an essential component. By joining the 21st Century education system innovators, I have used their approaches while creating the first three phases of performance authenticity: Pedagogy, andragogy, and heutagogy. The fourth phase is personal, so it emanates from each personal application of the "my research for my development" procedure, gaining greater self-authorization of a hybrid coach-play perspective from each passing.

I have been on this quest for over 50 years (since June 1968). Yes, I am old. But not until very recently, during my initial research for optimabowling.com, did it consciously occurred to me that the particular purpose driving my research and planning all these years was the problematic "student-teacher relation." Below I have included a snippet of the Norm Friesen article that first opened my eyes to this widespread issue, "pedagogical relation."

Research from, The pedagogical relation past and present: experience, subjectivity, and failure (2017)

“Abstract”

“The pedagogical relation, the idea of a special

relationship between teacher and child, has long been a central theme or

‘problem’ in interpretive studies of education, with the term having been established in English some 25 years

ago by Max van Manen. Speaking more broadly, themes of ‘student-teacher

relations’ and ‘pedagogies of relation’ are common in both empirical and

theoretical literature. The German educationist Herman Nohl (1879–1960) was the

first to give the phrase ‘pedagogical relation’ explicit description and

definition, and as I show, a steady stream of educationists have followed in

his wake. Nohl’s notion has subsequently been revised and criticized by

prominent continental scholars, and much from these continental

conceptions—particularly the exclusive focus on the child’s experience—has been

retained or strengthened in English by van Manen and others. However, in the

light of ongoing adult and teacher fallibility this paper argues that the

weakness, hesitation and subjectivity of the educator must also be accounted for in any understanding of the

pedagogical relation. In tracing the 90-year trajectory of this notion, the

paper consequently concludes that moments of ‘interruption’ and ‘hesitation’

must be seen as integral, not accidental, to pedagogy and its relations.”

“Introduction: the pedagogical relation and pedagogies of relation”

“In the

introduction to their edited collection, No

Education without Relation, Bingham and Sidorkin point out that ‘there is a

long philosophical tradition of emphasizing [educational] relations’ in

philosophy, going back as far as Plato or Aristotle. Speaking of these relations generically, Bingham and Sidorkin

highlight Martin Buber, Hans-Georg Gadamer and Martin Heidegger as providing

important, recent contributions to this tradition. Each of these three figures,

it turns out, was deeply influenced by Wilhelm Dilthey, who inaugurated the

human sciences and its disciplines, and who famously declared in 1888 that ‘the study of pedagogy … can only begin with the description of the

educator in his relationship to the educand’. Buber encountered

Dilthey’s ideas during his studies in Vienna; Heidegger’s teacher, Edmund

Husserl, had Dilthey as his supervisor, and Gadamer, in turn, was supervised by

Heidegger. Since Dilthey’s time, the pedagogical relation, the idea of a special, affectively charged relationship

between teacher and child, has been a central theme or more critically, a challenging

‘problem’ in the pedagogical branch of the human sciences

(Giesteswissenschaftliche Pädagogik; Klafki). In this context, it is

hardly incidental that Herman Nohl, the first to theorize the pedagogical relation,

was himself a student of Dilthey, and that he saw himself as consolidating a

‘movement’ in which pedagogy is investigated in terms of the relation between

educator and educand.”

“However, in saying that the ‘study of pedagogy’ begins ‘with the description of the educator in his relationship to the educand,’ Dilthey not only underscores the importance of student–teacher relations, he also identifies techniques of description as most appropriate for their study. In so doing, he can be said to have anticipated one of the fundamental tasks that reconceptualist curriculum theorizing as well as phenomenological research in education have set for themselves. This theorizing and research extends from William Pinar’s ‘method of currere’ (1975) to phenomenological studies of the student’s or teacher’s experiences as situated in their respective, everyday lived realities or lifeworlds. Speaking more broadly, Dilthey’s imperative also resonates with continued attention by psychometricians to ways of quantifying and standardizing measures of teacher–student ‘closeness, ’conflict’ and ‘dependency’. Given the attention converging from various quarters on this topic, it is valuable to revisit its conceptual origins in the work of Herman Nohl, and to see how his original understanding has been subsequently affirmed, adjusted and critiqued.”

“Underpinning Nohl’s influential conception is an affirmation of the primacy of the experience of the student and teacher, and in particular, an inversion of their ‘traditional’ order or structure: Instead of the teacher’s experience, expectations and concerns dominating the pedagogical situation, it is only those of the young person or child that are significant. After describing this and other key points from Nohl’s texts, this paper provides an overview of post-war continental critique and revision of the pedagogical relation, and then traces its reception and interpretation in English. I argue that these interpretations run up against a difficulty inherent in the pedagogical relation since its inception: The ultimately unfulfillable obligation that the exclusive focus on the child’s experience and subjectivity places upon teachers and adults. Finally, by highlighting work by O. F. Bollnow, and more recently, by Andrea English, Gert Biesta and others, I argue that in the light of adult weakness and fallibility, a second fundamental ‘inversion’ is required in the pedagogical relation. This is one in which we, as pedagogically engaged adults, experience our own ‘interruption’ and ‘hesitation,’ and are thus thrown back onto our own subjectivities, experiences and weaknesses—as well as onto the broader institutional and political context in which they are manifest.”

Teacher and Student as A Collective Control Process:

To move this teacher-student relation discussion beyond pedagogy and adult-child relationship. The research topic I am studying is the "collective control process." Next, you'll find the Collective Control page. Most of the material therein was drawn from the 2011 paper by Kent Alan McClelland. He introduced the collective control process, which I am utilizing as the premise of my discussion, to help us understand and resolve the misunderstood, dynamic coach-athlete relation.

I will also be reading what looks like a great resource, The Interdisciplinary Handbook of Perceptual Control Theory, Living Control Systems IV (2020), Edited by Warren Mansell—focusing on Section C: Collective Control and communication.

See More: The Collective Control Process

Back To: Inner and Outer Freedom

Back to: Coach Education for Maturation

Back to: Bowling Academy